What Causes Your Tears of Pride?

Tears come upon people for many various reasons. Psychologists, generally speaking, categorize tears into “negative” and “positive” tears, all in context of the physical reasons for said tears. Tears are the physical response of the brain’s cognitive reaction to the environment it senses; therefore, tears can be for negative (death, destruction, and depression) and positive (achievement, happiness, and affection) reasons.

Albert Richard Smith, an English author, said it best: “Tears are the safety valve of the heart when too much pressure is laid on it.”

A smart man or woman knows that tears are in response to the horrors or encouragement that surrounds them, but a wise man or woman understands their power.

Military members are extremely aware of tears of loss regarding slain colleagues from combat, accidents, or their own hands. Moving every three years and losing the comfort and security we establish in a unit or a group of friends all to do the heavy investment in new personal relationships challenges how we perceive human nature and value our friends and family. Watching death and destruction around us; children digging through garbage to maintain their lives in abject poverty. Watching convoys carrying aid and supplies to aid the civilian populations be destroyed killing your colleagues. Constant stress, lack of sleep, make no mistakes, toxic work culture, and a fear of being the weak link in your unit pushes our minds to the limit.

These described items are trauma. Trauma is the equivalent of physical assault on the brain. When the brain processes the various forms of stimuli the follow-on emotions need to be further processed or they will build in the mind like lactic acid from a heavy workout without stretching. We will drink, smoke, workout, turn to art/music, or cry to process emotions.

The most under appreciated tears though are those positive tears; little attention is given to this physical response. There are multiple times in our careers where we have also had times of achievement, joy, or admiration but do we rarely ever share those stories with each other. This article is the author’s attempt to share an occasion where he cried tears of pride and joy for being a member of the United States military. These were events that transcended logic and emotion to a level that made him appreciate the existence of the use of force and power.

Dachau was the first concentration camp the National Socialists in Germany opened in a small village northwest of Munich, Bavaria on 22 March 1933. Originally intended to be a political prison for those who challenged the National Socialists, Dachau housed communists, social democrats, and homosexuals all who were all subject to forced labor. Overtime, the camp’s population expanded to include Slavs, Jews, Roma, and other ethnic groups from occupied areas to the East as did the torture and medical experimentation on the populace.

Dachau was the “model” camp and over the next twelve years it was estimated the camp housed over 188,000 prisoners with an estimated 41,500 deaths. The war exacerbated conditions as more and more people were shipped to the primary or secondary locations, which worsened living conditions: less food, more torture, and forced labor.

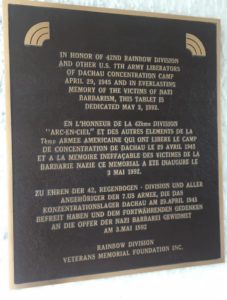

On 29 April 1945, U.S. Army personnel from the 45th Infantry Division were ordered to secure the camp while the 42nd (Rainbow) Infantry Division accepted the surrender of the camp liberated 30,000 personnel. This was not the first liberated concentration camp; the Soviet Union liberated Majdanek near Lublin, Poland on 22 July 1944. Additionally, the Soviet Union liberated Auschwitz on 27 January 1945 in which historians have agreed is the worst of the Nazi concentration camps.

The United States military did its fair share sacrificing thousands of soldiers and seamen ending the National Socialists in Germany and in turn freeing hundreds of thousands of people.

I visited the Dachau Concentration Camp on my birthday, 29 March 2018. It was a gift to myself, taking a day off work and exploring southern Germany alone. The journey that day had no specific destination, except the drive from Stuttgart to Munich along the A8. Tucked away in a quiet part of metro Munich is the small town of Dachau that hides along its streets the concentration camp. One walks from the parking past the visitors center and through the trees along the path is a stone building, clearly from the early 20th century with an arched entry and steel gate.

“Arbeit Macht Frei” is in steel above the door. The arched tunnel focuses foot traffic to this door that the Germans used as a reminder for those brought to the work camp. To the left though were two plaques placed to commemorate the day and time when U.S. military members entered the camp.

I sat there reading these plaques juxtaposed against the steel gate. People were taking pictures, reading, and commenting in several languages. These people were there to see what remained from a factory of death; these metal plaques reminded those who came through the gate it was the U.S. military that prevented others from entering as slaves. It was not the militaries of these peoples’ countries, but mine; we had liberated this camp saving tens of thousands and making peace.

My eyes watered but were quickly wiped clean to ensure no one asked questions.

Entering through the gate into the large gravel quad feels rather confining. The remaining buildings contain terrific historic exhibits about the rise and fall of the Third Reich along with the contextual background of the concentration camp. At far end of the camp past the now empty rows that used to contain occupant housing, lie the international prayer and meditation buildings which beautifully balance the crematoriums which hide amongst the trees.

That day was cold and cloudy, making the buildings cold. If one opens their mind and heart to those things around them, they will their senses allow them to fully appreciate what they experience. This made the next three hours transcendent to the full experience of Dachau and thus the tears that were shed over the next three hours while walking around the complex. I sat in the each of the houses of prayer and contemplated about the stories of hope and resilience; how people survived given the torture and depravity.

Not sure who many visitors witnessed me walking around that day could guess if I were U.S. military, but it was clear they saw me someone with red eyes wiping away tears.

But why? Why would a United States Air Force officer who never saw combat be so moved to something like this?

Growing up a preacher’s kid and then later being bullied in my early teenage years, there has something to be said about feeling like there is no one there to help you. Some of my favorite movies and books have to do those teams or individuals who rescued those who who faced a no-win scenario. There is something validating witnessing the use of force to help those who need help; even those heroes who are not perfect (reference the movie Unforgiven).

When faced with death, my spirit was elated knowing the people who faced these horrors were rescued; those rescuers just happened to be U.S. military members, the organization to which I belong. I choose to be part of an organization that used its resources to rescue a people that were unfairly persecuted. This is what defines heroes, even if this was only a secondary reason to a primary strategic reason.

The question in all my international relations classes come back to a simple question, “When should the U.S. use its military power for the benefit of people’s lives?” This is a tough question to ask because underpinning many of these discussions relate back to what is the larger context of geopolitics. Decisions are never as easy as they seem.

Pred

A 19 year Active Duty Air Force Officer who has deployed twice to Guam as a B-52 crew member and to Mali as a United Nations Peacekeeper.